Sound of Silence

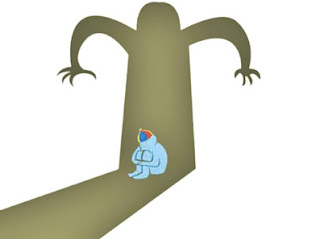

I noticed his eyes were unflinching when he told me in Nepali, “I was sexually abused at the age of 12 and from that time, I have never had any sexual relations. Now I am 28 years old.” I was speechless for a second, absorbing every word he said. In front of me was a young man who was alleged to be homosexual after not engaging in any serious relationship with a woman. His struggle to be in a relationship was the result of a dark past that haunted him for sixteen years.

The year was 1999 when CPN-UML leader Yadu Gautam was assassinated by Maoist insurgents. This was followed by an explosion at the offices of the Election Commission and Gorkhapatra, the widest circulated Nepali newspaper, in Kathmandu. The country was in peril and everyone aspired to a secure future. Rupesh (name changed) was a 12-year-old boy from Terhathum district in eastern Nepal. As in most cases, he was sent to an English boarding school outside his village to pursue a better education.

I asked Rupesh how he met the perpetrator. He said that the man lived in front of his single room hostel, next to the house of his maternal aunt’s sister. Rupesh was a tuberculosis patient and his aunt administered his medicines. With his daily routine of taking prescription drugs, he encountered this man every day.

“I used to read newspapers in his office where he worked as a government worker. That day, he asked me to read inside his room while he fixed an electric bulb. He then removed my underpants and raped me,” said Rupesh. The next day, he ran and escaped from the same guy’s attempt to sexually abuse him. Rupesh swallowed his tuberculosis medicine without water, locked himself in his own room, terribly terrified and still bleeding from the attack.

How can anyone not hear this story in disgust? Rupesh’s exposé shows what is profoundly wrong with child molestation. His sexual abuse and its aftermath has caused ill effects such as depression, anxiety, guilt, fear, sexual dysfunction, withdrawal and fear of the opposite sex. In worst cases, the tides turn when children hit adolescence wherein they display inappropriate sexual behaviour.

Based on studies, a majority of child sex abuse cases go unreported because of its stigmatic nature, even more so if they involve young boys. Child friendly mechanisms of psychosocial support for children who have been sexually abused are critically important. Child Workers in Nepal (CWIN), established in 1987, is an advocacy organisation for child’s rights with a focus on children living in and working under difficult circumstances. When I visited CWIN earlier this year, their Child Helpline Nepal had registered 447 cases (from January to June 2013) of boys being subjected to sexual exploitation, physical abuse, labour and child marriages. This number continues to rise despite CWIN’s toll-free hotline, ambulance service, counseling, emergency shelter, medical and legal services are used as tools for child welfare.

Another report by Save the Children Nepal in 2003 validated that nearly 13.7 percent of the 5,000 interviewed students had suffered from severe sexual abuse. This data must have been doubled by now and you need not go far to see the proof. Major streets in the Bir Hospital area, Bus Park, New Road, Basantapur, Gaushala, Thamel, Chhetrapati, Durbar Marg, Kalimati and Kuleshwor are frequented by street children who become victims of daily sexual abuse. This gives us the face of a social malaise that should collectively move us to public outrage or stoke us to stop it.

But clearly, these are not enough, not by any stretch of the imagination. In Nepal and its surrounding regions, there still exists a culture of silence where child sexual abuse is often viewed as something that should not be talked about, even if it is happening in close proximity. Much of this stems from cultural notions of shame and family honour that can be a matter of life

and death, especially for girls. More so, children are often confused as to whether non-penetrative forms such as touching or fondling are affectionate displays of love or abuse.

In Nepal, counseling interventions for sexually abused children are usually done by indigenous healers before consultations with formal health workers due to lower costs involved. Clearly, there is still a lack of awareness about the role of counseling within the broader healing process of the abused child.

Rupesh currently works with a peace and human rights organisation based in Kathmandu. While his institution actively works in the pursuit of human rights and justice, his troubled past remains hidden inside his closet. I challenged him to speak out. I quoted former US President John F Kennedy, “The rights of every man are diminished when the rights of one man are threatened.”

It is not enough to say that as long as we perform a puja (worship) for prayaschit (repentance), we can rape and still call ourselves holy. Self-proclaimed god men who sexually abuse young children deserve to be behind bars. The cruel man who sexually abused Rupesh walks free and is still raping other innocent boys. Rupesh seemed to agree with me on this and said, “I do not know where he is posted now but his name can be found from looking at his office file during that time. If he is found, I would like to expose him and put him behind bars.” At long last, there is hope for justice.

Cabrido is an international news stringer assigned in Kathmandu (chincabrido@gmail.com)

Posted on: 2013-09-17 08:55

Posted on: 2013-09-17 08:55

Kathmandu Post

http://www.ekantipur.com/2013/09/17/opinion/sound-of-silence/378107.html

Comments

Post a Comment